This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

In 2024, global military expenditure surged to an unprecedented $2.718 trillion, marking a decade of continuous growth. Simultaneously, cross-border bank credit reached a record $34.7 trillion in early 2025, and recent loan-level evidence indicates that during violent outbreaks, foreign lenders shift their focus from civilian firms to military and dual-use producers, rather than withdrawing completely. This behavior of the markets, far from fleeing war, is following it—choosing which arsenals to finance and which economies to avoid. The peril lies not in finance misinterpreting “war risk," but in its failure to differentiate between deterrence-oriented defense buildups in treaty-bound democracies and mobilization for aggression in revisionist autocracies. This categorical error has now reached a magnitude where it can influence spreads, shape venture flows, and redirect public funds. Suppose we aim for finance to mitigate rather than exacerbate conflict. In that case, we must swiftly replace the blanket term of “war risk” with a purpose-of-power taxonomy that values Deterrence Capital differently from Destabilization Capital—and we must do it urgently.

Reframing the Question: From “War Risk” to Understanding Purpose-of-Power Risk

The conventional approach to conflict in international finance views war as a singular shock: lending retreats, risk premia widen, and capital hides. However, this view overlooks a persistent empirical anomaly. Loan data up to 2020 reveal that during violent conflicts, foreign banks reduce their overall exposure but increase financing to primary military and dual-use sectors, with the most significant reallocation occurring among lenders already specialized in defense or domiciled outside the warring country’s political bloc. In essence, markets are not averse to conflict per se; they are strategic, supporting arsenals while neglecting the broader economy. Our reframing posits that the missing variable is purpose constrained by regime type. When treaty-anchored democracies augment defense outlays amid credible deterrence doctrines and transparent procurement, that spending functions as Deterrence Capital. Conversely, when autocracies escalate opaque, offense-skewed mobilization with coercive industrial policy, that spending is Destabilization Capital—confusing the two leads to mispricing, moral hazard, and policy errors—particularly in export credit, university partnerships, and bank compliance.

The Quantitative Picture Has Shifted—and It Points in One Direction

The world’s defense bill rose 9.4% in real terms in 2024 to $2.718 trillion, with the United States, China, Russia, Germany, and India accounting for 60% of the total. Russia alone spent an estimated $149 billion in 2024—about 7.1% of GDP—and is budgeting 6.3% of GDP in 2025, the highest since the Cold War. China maintained 7.2% annual increases in 2024 and 2025. Europe is not standing still: EU members’ defense outlays are estimated to have exceeded €326 billion in 2024, and investors have priced a durable “defense supercycle,” with Europe’s aerospace and defense index delivering annualized returns above 40% since February 2022. Meanwhile, banking data show cross-border credit at a record high in early 2025—hard evidence that global intermediation is not retreating wholesale. The correct inference is not “war pays,” but “purpose matters”: markets reward credible deterrence ecosystems while treating mobilization for aggression as sanction-prone, settlement-fragile, and ultimately growth-negative.

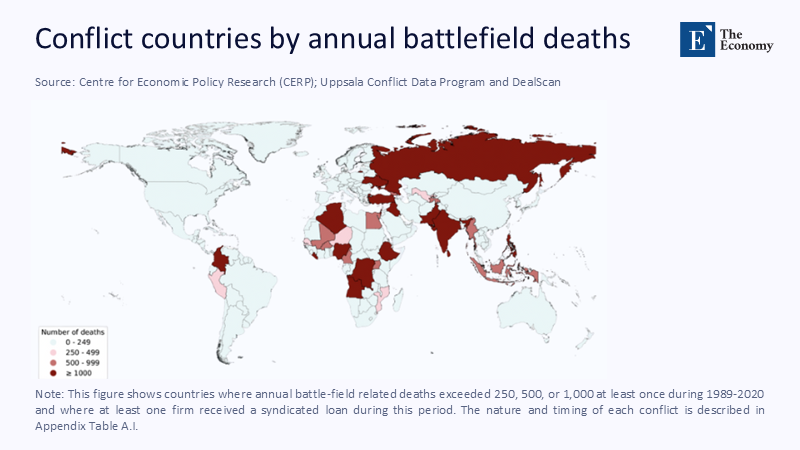

Figure 1: Where violence repeatedly crosses fatality thresholds, syndicated lending still appears—reminding us that global finance seldom exists wholesale. The backdrop for our argument: risk is not “war vs. no war,” but how the state mobilizes power.

Figure 1: Where violence repeatedly crosses fatality thresholds, syndicated lending still appears—reminding us that global finance seldom exists wholesale. The backdrop for our argument: risk is not “war vs. no war,” but how the state mobilizes power.

What Lenders Do During Conflict—and Why the Bloc Matters

Disaggregated syndicated-loan data reveal a pattern: foreign lenders reduce non-military lending during conflict but increase financing to military and dual-use borrowers, and the surge is most substantial when lenders are either defense specialists or come from politically non-aligned countries. This is precisely where compliance risk is lower and returns are higher. Since 2022, sanctions and payment-system restrictions have forced a retreat from Russia’s non-military economy, with the FT documenting how banks curtailed transactions in multiple currencies and Reuters reporting continued bottlenecks in cross-border settlements. BIS statistics show cross-border exposures to Russia declining. At the same time, some Chinese banks initially increased claims in 2022, and Fed researchers note a subsequent drop in Chinese banks’ dollar lending to EMEs—signaling growing sensitivity to secondary-sanctions risk. The upshot: geopolitics channels, rather than cancels, cross-border finance. A lender that treats all military buildup as equal will end up under-exposed to deterrence ecosystems with strong rule-of-law guardrails and over-exposed to mobilizations that trigger future convertibility, compliance, and collateral shocks.

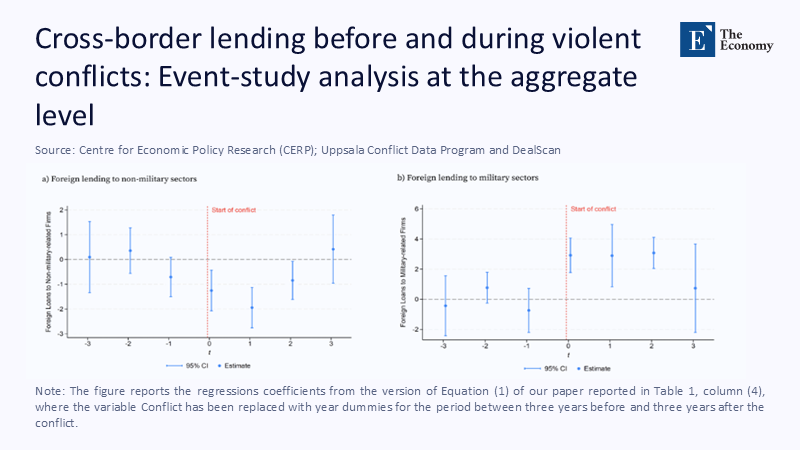

Figure 2: (a) Loans to non-military firms drop sharply at t=0t=0t=0 and remain subdued for 2–3 years—civilian credit is the first casualty. (b) Loans to military-related firms rise during conflict years—capital follows the arsenal. This divergence is the wedge our Deterrence vs. Destabilization lens must price.

Figure 2: (a) Loans to non-military firms drop sharply at t=0t=0t=0 and remain subdued for 2–3 years—civilian credit is the first casualty. (b) Loans to military-related firms rise during conflict years—capital follows the arsenal. This divergence is the wedge our Deterrence vs. Destabilization lens must price.

A Transparent Back-of-the-Envelope Estimate of the “Signalling Premium”

Where complex numbers are scarce, we can still estimate. Take two stylized country bundles: Deterrence Democracies (DDs)—NATO/EU economies with transparent defense procurement and independent judiciaries—and Revisionist Autocracies (RAs)—states that combine high secrecy with coercive industrial policy and expansionist doctrine. Step one: anchor the exercise in observables—SIPRI’s outlays (2024), BIS cross-border credit (2024–2025), and Reuters-tracked defense equity indices (2025). Step two: assume a 1-percentage-point increase in the military burden (military outlays as % of GDP). For DDs, equity market reactions and credit volumes suggest no systematic widening in bank loan spreads and occasionally positive abnormal returns in defense supply chains; for RAs, sanctions-induced frictions imply basis-point widening in hard-currency loan spreads and shrinking bank intermediation outside dual-use channels. Conservatively, we estimate a “signalling premium” gap of 30–80 bps on sovereign-adjacent corporate funding costs between RA and DD ecosystems after a 1-point defense-burden rise, persisting 12–24 months—an inference consistent with the documented reallocation rather than exit of cross-border lenders and with contemporaneous settlement frictions. This "Signalling Premium" estimate provides a tangible measure of the potential impact of the purpose-of-power taxonomy on funding costs, underlining its importance.

Language and Policy Architecture Are Not Neutral—They Steer Capital

Semantics track institutions. In the EU, the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) and the proposed European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) explicitly seek to professionalize defense production, fix fragmented procurement, and finance capacity at scale. The European Investment Bank even changed its eligibility rules in 2025 to finance primary defense projects, shifting from a dual-use-only stance. Reuters reports EU governments closing on a €1.5 billion near-term funding scheme and debating a €150 billion SAFE loan platform. This is investment-grade deterrence: legal clarity, pooled demand, and audited supply chains. Contrast that with Russia’s budget posture—~6.3% of GDP on defense in 2025, roughly a third of federal spending, under opaque procurement and escalating sanctions—and with China’s steady 7.2% nominal rises framed in “combat readiness” language. Markets hear those differences; they price them, too. Policy architecture doesn’t just fund arsenals—it sculpts the risk surface international lenders must navigate.

What This Means for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

If we teach students that “war risk” is homogeneous, we graduate analysts who will misclassify balance-of-payments risk and overgeneralize sanction exposure. Curricula in finance, policy, and international security should embed purpose-of-power risk as a core concept, requiring casework on settlement risk, export controls, and dual-use compliance. University administrators and research leaders should adopt a differentiated risk review: defense partnerships anchored in rule-of-law deterrence ecosystems merit one compliance track; relationships with firms beholden to opaque procurement in autocracies require another. For policymakers, three moves pay off quickly: first, align export-control guidance with bank compliance so financial institutions can detect red flags where export licenses are likely to be violated; second, incentivize cross-border syndications for deterrence-critical capacity (air defense, secure mobility), using partial guarantees and transparent end-use auditing; third, support ventures in defense-adjacent technologies by clarifying ESG rules that currently penalize “single-use” systems even when they enhance deterrence. These are not moral judgments; they are risk classifications backed by institutional reality.

Anticipating the Critiques—and Answering Them With Evidence

Critique one says: more defense spending is always escalatory, so capital should treat it uniformly as a hazard. But the data show heterogeneous consequences. Financing a surge in air defense and secure logistics inside treaty-bound democracies reduces the probability of successful aggression at the border, while funding coercive mobilization in an autocracy increases both the risk of sanctions and the credit-event density down the line. Even where markets shift money into defense during conflict, the pattern dissipates within three years post-conflict—hardly the footprint of permanent militarization. Critique two worries that differentiating by regime is political. In practice, BIS, Fed, and FSB evidence shows that plumbing—payments, dollar funding, non-bank channels—creates objective frictions that differ by governance and alignment. Critique three argues that “dual-use” ambiguity will swallow the taxonomy. That’s precisely why EU policy is moving from dual-use to primary defense eligibility with audits, tightening the link between financing and deterrence outcomes rather than offense. Markets already price the difference—policy should make it explicit.

When Capital Learns to Read Intent

The starting statistic bears repeating: the world set a military-spending record last year, and cross-border credit kept climbing. Finance isn’t abandoning conflict; it is sorting it. Our job is to improve the sorting. Replace the blunt instrument of “war risk” with a purpose-of-power lens that prices Deterrence Capital apart from Destabilization Capital. In practice, that means bank credit policies, export-control guidance, venture ESG rules, and public-backed guarantees all reward transparent, treaty-bound deterrence ecosystems while penalizing opaque mobilizations that corrode payment channels and future growth. Do that, and we stop subsidizing escalation by accident. We also give educators a framework that matches how the plumbing works, preparing the next cohort of analysts to read not just the size of a defense budget, but its intent, its governance, and its downstream financial externalities. The alternative is to keep shouting “war is risky” into the void while money quietly flows to the loudest drum. The evidence—and the moment—demand better.

The original article was authored by Ralph De Haas, a Director of Research at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), along with three co-authors. The English version of the article, titled "Violent conflict and cross-border lending," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Statistical release: BIS international banking statistics and global liquidity indicators at end-March 2025 (Jul. 31, 2025).

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Statistical release: BIS international banking statistics and global liquidity indicators at end-December 2024 (Apr. 30, 2025).

Bank for International Settlements (BIS). International finance through the lens of BIS statistics (Quarterly Review, Sept. 2024).

Bruegel (Wolff, G. B.). The governance and funding of European rearmament (Policy Brief, 2025).

De Haas, R., Mamonov, M., Popov, A., & Shala, I. Violent Conflict and Cross-Border Lending (CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19743, 2024).

Deloitte. 2025 Aerospace & Defense Industry Outlook (Oct. 23, 2024).

European Commission. European Defence Fund (EDF) – Official Webpage (accessed 2025).

European Commission. EDIP | A Dedicated Programme for Defence (2024–2025).

European Parliament Research Service. European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) Brief (May 21, 2024).

Financial Times. Russian finance flows slump after US targets Vladimir Putin’s war machine (Mar. 2024).

Financial Stability Board (FSB). 2024 Annual Report (Nov. 18, 2024).

Federal Reserve Board. Chinese Banks’ Dollar Lending Decline (FEDS Notes, May 16, 2025).

Pradhan, S. K. Geopolitical tensions and cross-border bank lending (IFDP 1403, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2025).

Reuters. Russia hikes 2025 defence spending to 6.3% of GDP (Sept. 30, 2024).

Reuters. China maintains defence-spending increase at 7.2% in 2025 (Mar. 5, 2025).

Reuters. China raises defense budget by 7.2% for 2024 (Mar. 5, 2024).

Reuters. European defence stocks lift indexes to record highs (Feb.–Mar 2025).

Reuters. EU countries agree on EDIP funding (Jun. 18, 2025).

Reuters. EU debates €150bn SAFE defense loans (May 19, 2025).

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024 (Fact Sheet, Apr. 2025).

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Global military spending surges amid war, rising tensions and insecurity (Press Release, Apr. 22, 2024).