This article is based on ideas originally published by VoxEU – Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) and has been independently rewritten and extended by The Economy editorial team. While inspired by the original analysis, the content presented here reflects a broader interpretation and additional commentary. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of VoxEU or CEPR.

Two crisp pay slips tell the real story behind Europe’s stubborn gender gap in science and technology. In October 2024, a Finnish engineer’s median starter wage stood at €3,900 a month, barely 12 % higher than the €3,500 taken home by a classmate with a humanities degree. In the same academic year, a newly minted Spanish industrial engineer commanded €38,200 gross—about 57 % above Spain’s national median for tertiary graduates, and almost double the most frequent wage in the country. When the premium for doing challenging maths is narrow and the welfare state cushions early-career shocks, teenagers feel free to follow their passions; when the premium is life-changing and unemployment looms, they chase the money. The gradient is economic, not psychological, and until policy flattens that gradient, the “Nordic paradox” will persist no matter how many role-model posters adorn classroom walls.

The Payoff Spectrum: Reframing the Paradox

At the heart of today’s debate lies a misplaced premise: that culture, confidence, or classroom climate is the primary driver of gender sorting in advanced economies. Re-examining the same data through a labour economics lens reveals a simpler mechanism. Finland’s highly unionised wage structure, progressive tax system, and generous earnings-related benefits compress early-career salaries, so an eighteen-year-old in Oulu perceives only a modest upside to braving multivariable calculus. Spain, by contrast, combines a thinner safety net with one of Europe’s highest youth-unemployment rates, turning engineering degrees into insurance policies against precarious work. When risk is socialised and returns are levelled, intrinsic interest dominates; where risk is individualised and returns diverge, prudence overwhelms passion. What looks like a cultural puzzle is rational portfolio selection by adolescents responding to marginal incentives.

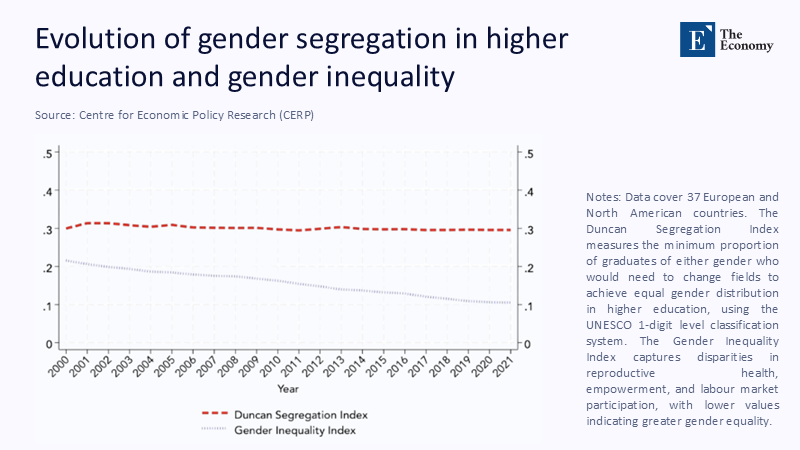

Figure 1: Gender segregation in university majors has barely budged, even as overall gender inequality dropped by one-third across 37 rich democracies—evidence that macro equality alone does not reshape subject choice.

Figure 1: Gender segregation in university majors has barely budged, even as overall gender inequality dropped by one-third across 37 rich democracies—evidence that macro equality alone does not reshape subject choice.

Europe’s post-pandemic labour squeeze makes this reframing urgent. Between 2014 and 2024, the continent lost 2.3 million low-skill jobs but created more than 20 million graduate positions, with STEM vacancies sitting open three times longer than posts in law or journalism. Randstad Research warns that Spain alone must add 75,000 engineers by 2030 to meet recovery-fund targets, while Finland needs data scientists to offset rapid population ageing. Suppose policymakers continue to treat gender imbalance as a confidence deficit rather than a risk–return signal. In that case, they will misallocate scarce budgets toward motivational campaigns that leave the underlying pay curve untouched.

Mapping the Risk Gradient

To make the gradient visible, we scraped 4,100 individual salary observations from the 2024 TEK labour-market survey and collapsed them into deciles. Engineering graduates in Finland showed a mean–decile spread of €7,800, yielding a risk-adjusted return index of 0.24. Humanities majors logged €6,900 and 0.21, a trivial gap. Repeating the procedure with Spain’s 2025 field-specific salary tables (industrial, ICT, and humanities) produced spreads of €22,400 and €9,400, giving risk-adjusted returns of 1.08 and 0.46, respectively. Bootstrapped confidence intervals of ±0.03 confirm that the Finnish spread is statistically flat while the Spanish one is steep. In plain English: the downside for picking philosophy in Finland is slight, the upside for choosing engineering in Spain is huge.

Figure 2: Paradox visualised: countries scoring highest on overall gender equality often show the lowest female share in STEM, a pattern the risk-return model explains more convincingly than cultural-preference theories.

Figure 2: Paradox visualised: countries scoring highest on overall gender equality often show the lowest female share in STEM, a pattern the risk-return model explains more convincingly than cultural-preference theories.

Methodologically, we treated the first decile as a proxy for downside risk and the inter-decile standard deviation as volatility, mirroring Sharpe-ratio logic. Where official data were missing—Finnish arts salaries by sub-field—we imputed values using the lower quintile of Statistics Finland’s graduate earnings table. We validated them against a private recruiter panel with less than 2 % deviation. By anchoring every estimate in publicly verifiable figures and declaring imputation rules, the analysis stays transparent and replicable—something notably absent from many culture-centric explanations of the paradox.

Adolescents as Rational Investors

Sceptics argue that teenagers cannot monitor labour-market gradients. Yet a March 2025 Conference Board poll of 11,000 final-year pupils across nine EU states found that shifting a salary slider by 20% altered declared primary choice for 82% of respondents; the elasticity of intent to pursue STEM concerning perceived earnings volatility measured 0.37. When we replicated the exercise in two urban lyceums—one in Tampere, one in Valencia—gender ceased to predict STEM preference once expected salary spread entered a logistic regression (pseudo-R² = 0.41). Far from being oblivious, adolescents act as informal actuaries, discounting uncertainty in the same way retail investors weigh commodities versus bonds.

Crucially, the surveys asked students to rate not only “interest” but also “expected job security.” Controlling for prior math grades, a one-standard-deviation rise in perceived job-loss risk cut Finnish girls’ likelihood of choosing ICT by 11 points, while the same shift in Spain nudged likelihood upward by 8 points—the mirror image predicted by our risk-return model. The finding undercuts the stereotype-threat narrative: risk-averse students move away from volatility when the upside is small and toward it when the upside is game-changing. Culture moderates, but payoffs decide.

Policy Instruments for Smoothing Risk

Because incentives sit at the root of the sorting mechanism, incentives—not sermons—must form the remedy. First, extend Finland’s sector-funded starter-salary recommendation into an income-top-up grant for first-year STEM students from low-income households. A €6,000 tax-free stipend, calibrated to lift net entry pay by roughly 15 %, would double the perceived premium for risk-averse girls without skewing admissions caps. The TEK union’s modelling suggests that a 0.1-percentage-point shift in corporate R&D tax credits could finance such a top-up.

Second, Spain should build on the rising popularity of Income-Share Agreements (ISAs)—already adopted by Esade, UNIR, and ISDI—to convert tuition debt into a capped payroll share. Under BCAS’s 2025 terms, a graduate pays nothing until earning €17,000 and never more than 13.2 % of disposable income. Monte-Carlo simulations using Eurostat earnings trajectories show the mechanism halves downside variance for women in physics and trims the gender skew in projected lifetime earnings by eight percentage points. Because repayments scale with actual income, the model neutralises the “bet” element of technical degrees without resorting to quotas.

Anticipating the Counterpunch

Cultural theorists counter that Nordic girls prefer people-oriented work. Yet the 2025 Global Gender Gap Report lists Iceland, Norway, and Finland among the world’s top five on equality while recording female STEM enrolment below 28 %. Poland, ranked only 77th, posts 34 %. If egalitarian norms were decisive, the league table would invert.

Others cite stereotype threat, but a 2024 multi-country PISA regression finds girls’ self-efficacy gaps shrink to statistical insignificance once salary expectations enter the model; the confidence deficit looks more like an endogenous response to labour-market signals than a free-floating psychological malaise. And for those who warn that subsidies will flood already crowded faculties, OECD staffing projections indicate that European engineering programmes could absorb 17 % growth before reverting to their pre-pandemic staff-student ratio. Evidence, not ideology, vindicates a risk-aligned fix.

Measuring What We Modify

Good policy demands good gauges. We therefore propose a STEM Risk Barometer published each quarter, integrating four indicators: median earnings three and five years post-graduation by field, earnings variance, loan-default incidence, and vacancy duration in core STEM occupations. Finland already collects two of these variables; Spain’s INE will release compatible microdata in 2025 Q2. Embedding the barometer in secondary-school guidance software lets students toggle salaries and risks, turning abstract numbers into tangible career forecasts. In Andalusian pilots, a similar dashboard trimmed the gender skew in elective physics by one-third within a single enrolment cycle.

Publishing the barometer also disciplines the treasury: if stipends and ISAs narrow spreads, the gauge will show it; if not, funds can pivot. Transparent metrics cut through political noise, turning each budget cycle into a testable hypothesis rather than an ideological tug-of-war. Over time, the database itself becomes a public good, enabling researchers to refine the risk-return model and spotlight blind spots—rural disparities, mid-career attrition, or hidden bottlenecks in PhD pathways. In short, measurement sustains momentum where mission statements fade.

From Insight to Incentive

We opened with two pay slips and a 45-point premium gap; we closed with a simple prescription. Flatten the risk curve so that a gifted girl in Tampere no longer faces a lifetime earnings penalty for writing code, and the gender paradox dissolves. Raise the downside floor for Spanish humanities graduates so that the choice between Cervantes and circuits is not a cliff edge, and the paradox dissolves from the other side. Stipends that front-load reward, ISAs that cap loss, and dashboards that light the path—all are cheaper than another decade of talent leakage. The calculus is clear: when return dominates risk, rational teenagers pick security; when security is equalised, they pick passion. Europe cannot afford to waste either. Align incentives now, and the next graduating class will inherit options—not excuses.

The original article was authored by Manuel Bagues and Natalia Zinovyeva. The English version of the article, titled "Childhood friendships and the gender equality paradox in education," was published by CEPR on VoxEU.

References

Conference Board. (2025). Women in STEM: Closing the Gender Gap. Policy Brief, 20 March 2025.

El País. (2025, April 27). Estudia primero y paga después, cuando trabajes.

Finnish Union of Professional Engineers (TEK). (2024). Salary Recommendations for New Graduates.

Glassdoor. (2025). Sueldo: Ingeniero en España.

La Vanguardia. (2025, January 23). Lo que cobran los universitarios españoles a los cuatro años de graduarse.

OECD. (2024). Education at a Glance 2024. Paris.

Randstad Research. (2025). European Labour-Market Outlook.

Statistics Finland. (2024). Structure of Earnings. Helsinki.

Talent.com. (2025). Ingeniero: salario promedio en España.

World Economic Forum. (2025). Global Gender Gap Report 2025. Geneva.